Arguments in Favour of Trying

Another Year

We’ve all peered through the doorway from one year into the next and performed the same ritual: a soft, polite curiosity asked to our friends — deflecting attention from our own new year thoughts — to recite a list of what they’ll do more of, where they’ll be, and who they’ll finally become once the calendar flips over. Sometimes I even start these discussions as early as mid-December, if I’m at a party with people I have no intention of finishing the conversation with.

Oh, fitness? I’m hoping to swim more. Eating better? Yes. I never really liked chocolate either.

To many people, goal-setting has become an exercise in maintaining a cosmic order — the exchange that if we are privileged enough to see the earth perform another rotation, then we owe it back to arrange our next year into a sort-of upward spiral of measured success criteria. Three months of fitness, two months back-packing, a marathon in June.

Of course, nobody ever mentions the real resolutions that they’ve spent the solemn march of Christmas privately negotiating with themselves — the shameful order of things that they’ll want to quietly erase from the past year.

In a world populated by goals that we set to please others, more can be done to think of trying new things as a vehicle for healthy personal change, and how to form goals in a way that actually survives contact with real life once we get there.

What We Owe

The earliest forms of goal-setting comes from a ritualistic obligation: in ancient Babylon, people made vows to the Gods at the start of the year — promises to repay debts, return borrowed tools, or fulfil familial duties. They faced externally, as promises to family and friends that bordered on the contractual. Fail to keep them, and you disappoint your family and are sent to Hell. When wrongs were made, cosmology was bent out of shape, and the resolution when committed functioned as a mechanism of order: a way of re-aligning individual behaviour with the rigid moral and religious structures that held Babylonian society together.

Three thousand years later and goals still provide this orientation, but in society without the same moral and ethical codes, replaced by a wider set of constraints and external pressures. Most goals are instead framed as acts of self-improvement; upgrades to your personality, body, and measured output. They ask us to become somebody else without the backbone of reason — and when these targets are missed, we interpret their failure as personal weakness rather than structural mis-design.

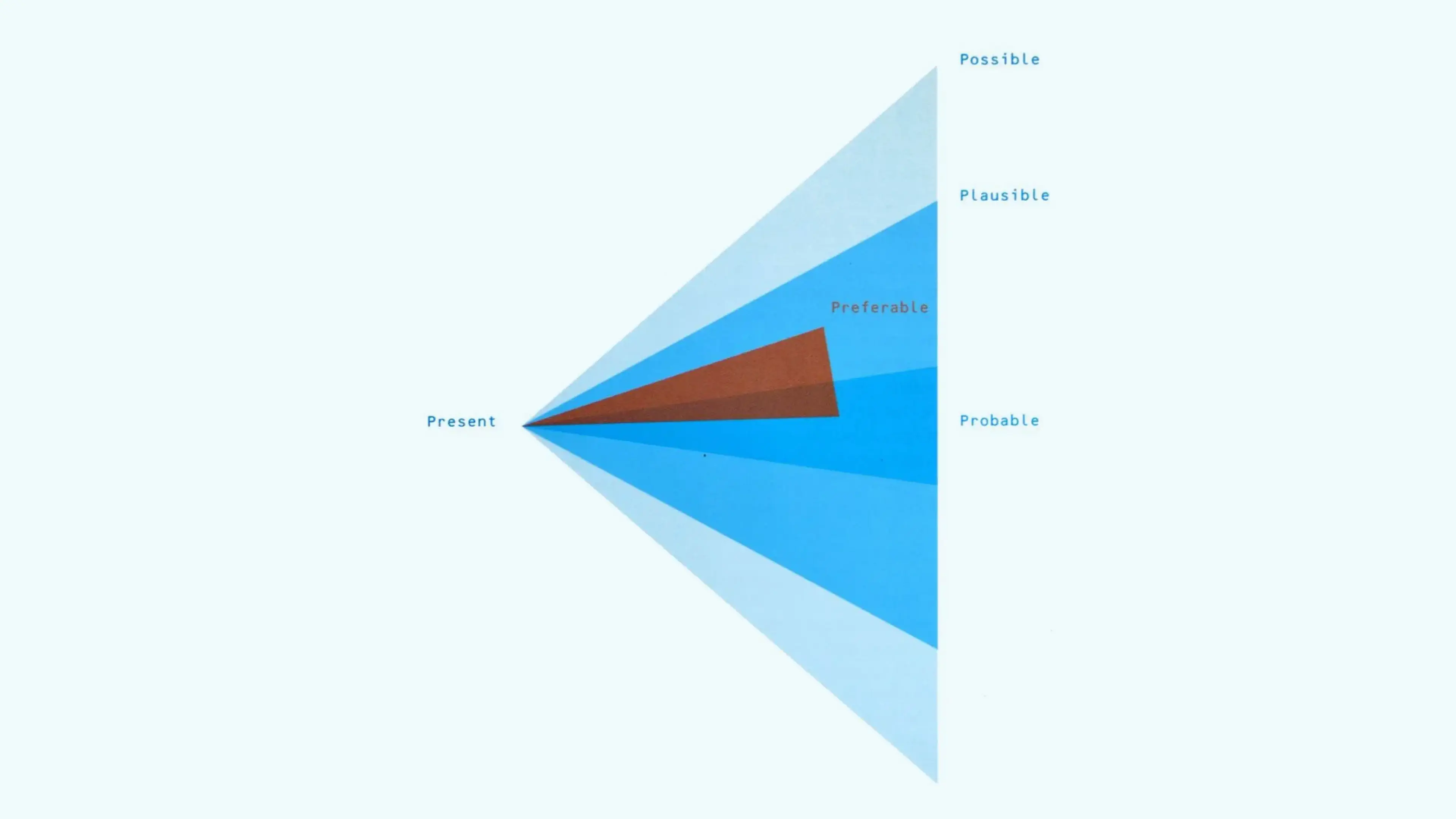

Goals remain the best tool we have for drawing boundaries around our behaviour — but instead I argue that we have lost the journey of trying new things in favour of doing everything perfectly for others. Reframing our wants around orientations, the question shifts from what do I want to achieve? to where do I want to go?

My Quiet List

Badly-formed goals fight bad behaviours head-on as a reactive symptom. Emerging under pressure: exhaustion produces goals about rest, loneliness produces goals about togetherness, and boredom produces goals about doing more. They point to where friction exists between the life you’re living and the one you’re capable of enjoying.

This is why traditional “Ins-and-Outs” lists often feel vapid. They treat symptoms as failures of discipline rather than signals that the surrounding environment needs re-shaping. As a serial goal-setter (and goal-misser), I have found a more useful approach is to treat the new year as an opportunity to adjust your operating environment: change the conditions that make behaviours inevitable, and they will no longer feel inescapable.

I’ve performed this exercise for 2026 by attempting to build plans which force my participation in a reality that aligns itself to where I want to go, rather than necessarily what I want to achieve.

Being Kind

I want to work harder to stop comparing myself to others. I can’t remedy comparing less in isolation, so instead I’ve been working on placing myself in situations where I will be able to put kinder eyes on myself day-to-day.

Beginning a new journey of learning a sport — especially one in a team setting — and committed to a weekly rhythm that celebrates attendance just as much as progress, means that spending the time results in the change I want to see, regardless of my final destination. I’m going to my first Ju-Jitsu class on Tuesday.

Being Flexible

“Vegan with Eggs” enables good not to be the enemy of perfect, in a world where many goals fail because they’re framed with completionism in mind. Living in an imagined future rather than a present body, they mistake the crowning achievement of a year of changes as the final impressive feat, rather than the slow and grinding wheels of built-up progress.

It’s an exercise in flexibility. Goals worth setting are rarely met in a swift single motion. They need tending, revisiting — occasionally abandoning — not to be watermarked as failure, but as feedback to play with. And like engaging with any new skill or pattern, trying a new thing while being open to failure enables healthier play rather than a rigid target that demands perfection every time. I’ve begun writing this blog.

Be Transparent

In the same way that the Babylonians made their vows before Gods to move their goals from mind-fiction to committed reality, I see transparency as a motivator in anything I’m willing to try. Before writing this post (which is also a form of transparency I’m exercising), I shared a much longer and more personal list of “2026 Manifestations” with friends. Oversharing? Yes. But accountable? I will have to be.

Suffering, so said James Baldwin, is a bridge — and so any time I have shared a vulnerability with friends of what I’d like to try without fear of failure, I have also found commonalities in their own 2026 plans — a journey which we now have the privilege of sharing.

A Commitment

Healthy framing of goals help close some doors so others may swing open fully. By living purposefully and deciding on an orientation rather than a defined target, you take meaningful steps that turn the next chunk of lived experience into one that always points in the right direction, regardless of your final destination.

So if I’m setting goals this year, it’s not to become someone new. It’s to reduce the distance between who I already want to be, and how I’m currently living. To begin trading delusion for realism, and to make fewer, but more intentioned promises — and keep only the ones I like.